This is the start of a series of blog posts. What follows is an introduction and Part 1.

I believe that artworks can only really connect with people at particular times in their lives. Ideally, a work of art has a profound impact the moment you see it for the first time, but this is rare. Other times you might see a great work of art that doesn’t connect because you’re not in a place mentally, emotionally, or intellectually to see its full depth. Sometimes the weight of a work hits you much later, when you or the conditions that surround you have changed in order to make a new reading possible. Perhaps the best case scenario is when a work has a big impact initially, and it also pops up again and again later in life, revealing new dimensions as it interacts with new versions of you, new times, new paths you walk. These works make sense in new ways as the world changes, and they help make sense of a changing world.

I’ve been thinking about new experiences with old art because we’re in a strange and precarious political moment. Donald Trump has been elected to return to the Whitehouse, but he hasn’t been inaugurated yet. We’re getting daily updates about truly horrendous cabinet picks and tariff threats. Trump has always been full of shit, so there’s no way of knowing which threats are real, uncertainty reigns. But it seems possible that the era of post-WWII American global dominance could be about to end, or change in a dramatic and negative way. It feels like the time between the Beer Hall Putsch and the invasion of Poland, to flog a tired historical metaphor. In any case, this all has me thinking about artworks that deal with destruction and iconoclasm on the one hand, and survival and renewal on the other. I’m wondering what will be broken, what will be saved, and what will eventually be rebuilt.

One exhibition that had a big impact on me when I first saw it, and keeps popping up to reveal new insights, is Documenta 13, an exhibition that I saw in Kassel, Germany in 2012. A lot of the artworks, images, and stories that are grabbing my attention in this Putsch/Poland moment somehow feel related to Documenta 13, either directly or indirectly. Documenta is a large contemporary art survey exhibition that has happened every five years since the end of World War II. The 2012 iteration was its 13th edition. As far as art experiences hitting at the right time in life, this one was a bullseye for me. It was the first really big biennial-style exhibition I had seen up to that point (other than a few Whitney Biennials, but those are really museum shows). I’ve since seen a few Venice Biennales and the two editions of Documenta that have happened since, 14 and 15, and Documenta 13 was by far the best of the bunch. The themes were rich and deeply intertwined by artistic director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev¹. It’s hard to summarize, but the duality of destruction and reparation was a common thread throughout the show. I often think about specific works from Documenta 13, but it has also become a sort of lens through which I see other artworks, images, and spectacles. It has a very prominent place in my art historical headcanon.

Part 1: The Vulgarity of Mount Rushmore

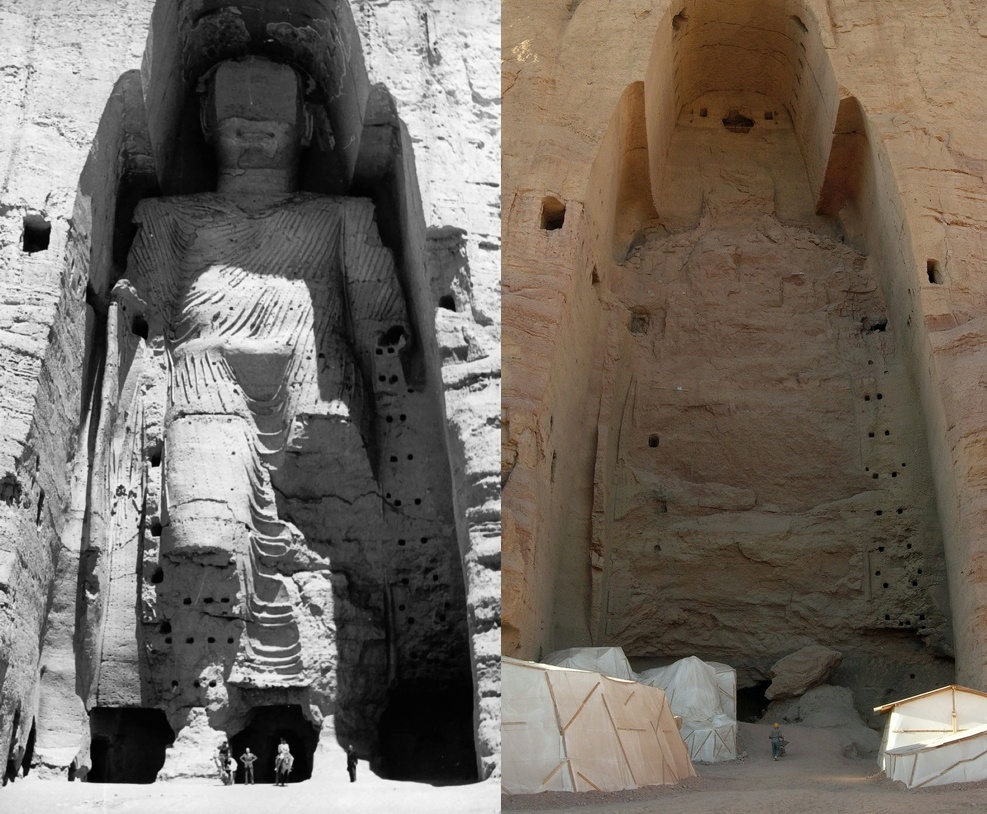

A few days ago a user on Bluesky² named Chad Loder posted, “The default example for destroying cultural heritage sites is always the Taliban’s destruction of Bamiyan’s buddhist statues, but never Mount Rushmore.” Followed by a wide aerial shot of Mount Rushmore along with, “When you view Mount Rushmore against the background of the sacred Black Hills site which it desecrated, you realize how hideous and pathetic it is. Truly a vulgar monstrosity.” The Bamiyan Buddhas were two enormous relief sculptures of Buddha carved into a cliffside in Afghanistan in the 6th century. They were both destroyed by the Taliban in March, 2001. Mount Rushmore, obviously, has not been destroyed. The point Loder was trying to make is that the creation of Mount Rushmore in the 1930s was a desecration of the natural mountain from which the sculpture was carved. The Black Hills area, which is home to the monument, is land stolen from the Lakota Sioux. The Lakota called the mountain “Six Grandfathers” long before the sculptor Gutzon Borglum began carving it up. In 1980 the Supreme Court ruled that the Lakota were not properly compensated for the land, and offered them $102 million. To this day the tribe has refused to accept the money, instead insisting that the land be returned. Accounting for inflation and interest, the sum is now nearly $2 billion.

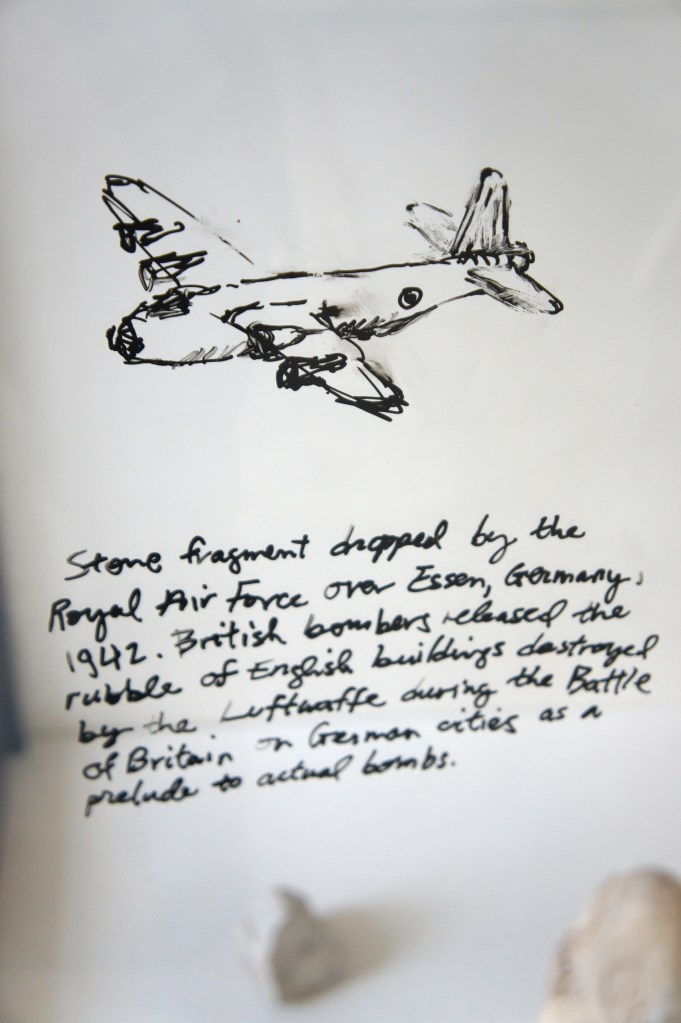

In Documenta 13’s main museum venue, the Fridericianum, the artist Michael Rakowitz presented an installation titled What dust will rise?. The room consisted of glass vitrines with artifacts and wood and glass tables holding carved stone replicas of books. The books were carved by Afghan artisans out of travertine that was quarried from the same cliff where the Bamiyan Buddhas stood for fourteen centuries before being destroyed. The forms of the books referenced real books that were once housed in the Fridericianum, which was a library before the war. The library, and much of Kassel, burned when it was bombed by the British Royal Air Force on September 9, 1941. The surrounding vitrines contained burned fragments of the real books, pieces of the destroyed Bamiyan Buddhas, and other ephemera, each object with its story handwritten on the protective glass by the artist. Above a small fragment of grey stone the artist drew a WWII bomber and wrote the text, “Stone fragment dropped by the Royal Air Force over Essen, Germany, 1942. British bombers released the rubble of British buildings destroyed by the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain on German cities as a prelude to actual bombs.” Think about that for a minute. A stone building in England is destroyed by German bombs. The Brits then take rubble of their own building with them on a bombing raid over Germany, and before hell rains down, they drop a simple stone, a small piece of what was lost, a little “fuck you.” I read this as an American in Germany in 2012, surrounded by stone books carved from Afghan travertine, standing in a museum that used to be a library until it was burned by Allied bombs. At that point our war in Afghanistan–our longest war ever, ostensibly a war against the destroyers of the Bamiyan Buddhas–had just reached its halfway point, although it seemed endless.

Back in South Dakota, Loder is right that something was destroyed when the four presidents were carved into the mountain of the Six Grandfathers. In Loder’s alt text for their image of Mount Rushmore they editorialize that the presidential faces look “small and pathetic against the stunning landscape of the Black Hills.” This is where I disagree. Mount Rushmore, despite the horrors of colonial conquest it embodies, actually looks pretty incredible. It looks triumphant, and it is triumphant, in the most terrible, bloody sense of that word. Borglum carved the faces of slavers and warlords in the mountain because he could. There’s something very American about that. There’s something terrible and impressive about who we are and it’s embedded in that stolen stone. The victories of those four presidents, as ill-gotten as some of them were, are also my victories, I inherit them whether I want to or not. What can we do to repair that? Give the Lakota their land back, for starters, but I’m not sure what else.

Considering Mount Rushmore as an act of destruction rather than creation makes me think that destruction and creation are closer than we might think. We build sculptures from the rubble of destroyed monuments. We turn burned libraries into museums. We drop pieces of bombed buildings onto buildings about to be bombed. We find poetic ways of stealing things and killing people. We preserve, we destroy, we rebuild, and we build monuments to big people and big ideas along the way. It’s tempting to think that we’re acting within history and that we are moving in one correct direction. But it’s more cyclical and confusing than that. Maybe Mount Rushmore can be triumphant and terrible at the same time. Art can be complicated, it can contradict itself. A sculpture called Shrine of Democracy, which is Mount Rushmore’s official title, can be carved out of a stolen mountain, without a shred of democratic input from the people the mountain was stolen from. But this is the country we have, and we have to do our best to make something good out of it. We’re all sifting through rubble, making what we can.

- Christov-Bakargiev is (weirdly!) a big fan of Beeple now, the NFT artist who makes terrible 3D renderings of Elon Musk and Trump with huge boobs. In fact I saw Christov-Bakargiev and Beeple together at a party at Documenta 15.

- Speaking of destruction and renewal, Elon Musk has fully killed Twitter and Bluesky has blossomed into a wonderful social network (if such a thing can exist).

One thought on “What Gets Broken, What Gets Saved”

Comments are closed.