Every December I write a blog post about the best art I saw that year. My previous job used to take me to contemporary art hotspots like the Venice Biennale, New York, and Art Basel Miami Beach. I don’t often make it to those places in my current line of work, but I still get to travel, so I’m always looking at art in one way or another. As a result, this year’s list is probably the least contemporary I’ve ever done. The most recent piece that I can confidently date was made in 1991, and most are much, much older. These works are not ranked, they’re listed in the order in which I saw them.

- Robert Morris, Earth Projects: Burning Petroleum (1969), Grand Rapids

The Grand Rapids Art Museum had a show of works from its collection that all dealt with the idea of maps in one way or another. It was a nice little show, more surprising than I would have thought. There were a few works on paper by Robert Morris, diagrams of earthworks both real and fictional. The local connection here is that Grand Rapids is home to a Robert Morris earthwork called Grand Rapids Project X (1974). It’s mostly forgotten now, and people who use the baseball diamond next to the work probably wonder why there’s a giant asphalt X cutting across the hill by the outfield. The map show had drawings of the X piece. But what really caught my eye was a large diagram of an earthwork that was never realized (fortunately) called Earth Projects: Burning Petroleum – From Liberal, Missouri Quadrangle, 1969. The print is from a portfolio of ten proposed earthworks, each of them ridiculously ambitious and/or destructive. Morris was interested in creating works based on phenomena that can only be experienced outdoors, and works that could not be perceived all at once. That’s all well and good, but this particular schematic proposed a work that would involve installing a buried tank of petroleum near a river, then pumping the oil onto the river and lighting it on fire. Essentially creating a real life river of fire, in Missouri I guess? I love this piece because it’s batshit insane. The print itself is understated, and in a show of maps it is indeed a map. But a closer look reveals that Morris is proposing an artwork that is incredibly environmentally destructive. It’s good it never happened, but I still love that he thought it up and diagramed it out.

2. Tribune Tower, Chicago

I took a trip with my family to Chicago and one morning I decided to wander aimlessly to look at buildings and whatever else I could find. Not far from my hotel I was delighted to find Tribune Tower. The neo-Gothic skyscraper was built in the 1920’s to be the home of the Chicago Tribune newspaper and related companies, which it was until 2018, when–depressing sign of the times incoming!–it was converted into luxury condos. But it’s still a very beautiful building. What caught my eye was the fragments of stone and bricks from other famous buildings around the world that are embedded in the exterior walls at the sidewalk level. There are chunks of Notre Dame de Paris, Angkor Wat in Cambodia, Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, and even not so distant structures like Wrigley Field. During the construction of the tower the owner of the Tribune instructed correspondents for the paper to bring back bricks and stones from famous buildings in the cities where they were reporting. How these reporters managed to obtain a stone from the dome of St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, or a gargoyle head from the House of Parliament in London, is a mystery to me. In any case, the fragments make for a great architectural detail that operates on a human scale.

3. Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991), Chicago

Normally with these lists I only include works that I encountered for the first time this year, even if they’re old. That’s not the case here. I’ve seen many of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ works before, including many of his various candy piles, including this particular one. The reason I’m featuring it on this list is because it was the first time I was able to show this work to my children, explain the story behind it, and invite them to take a candy. If you’re unfamiliar, this is one of several works that Gozalez-Torres made that were “portraits” of specific people that consisted of piles of candy that corresponded to each subjects’ weight. This one refers to the artist’s partner Ross Laycock, who died from complications of AIDS in 1991, the year this work was made. Visitors are encouraged to take a candy and eat it, thereby diminishing the size of the pile. The museum replenishes the pile periodically so the participatory nature of the piece can continue. Gozalez-Torres also died of AIDS a few years later, in 1996.

It meant a lot to me to show this work to my kids, they seemed to understand its gravity. They listened in a way that went deeper than just humoring dad while he rattles on about the stuff he’s into. It’s hard to talk to kids about death, but art helps.

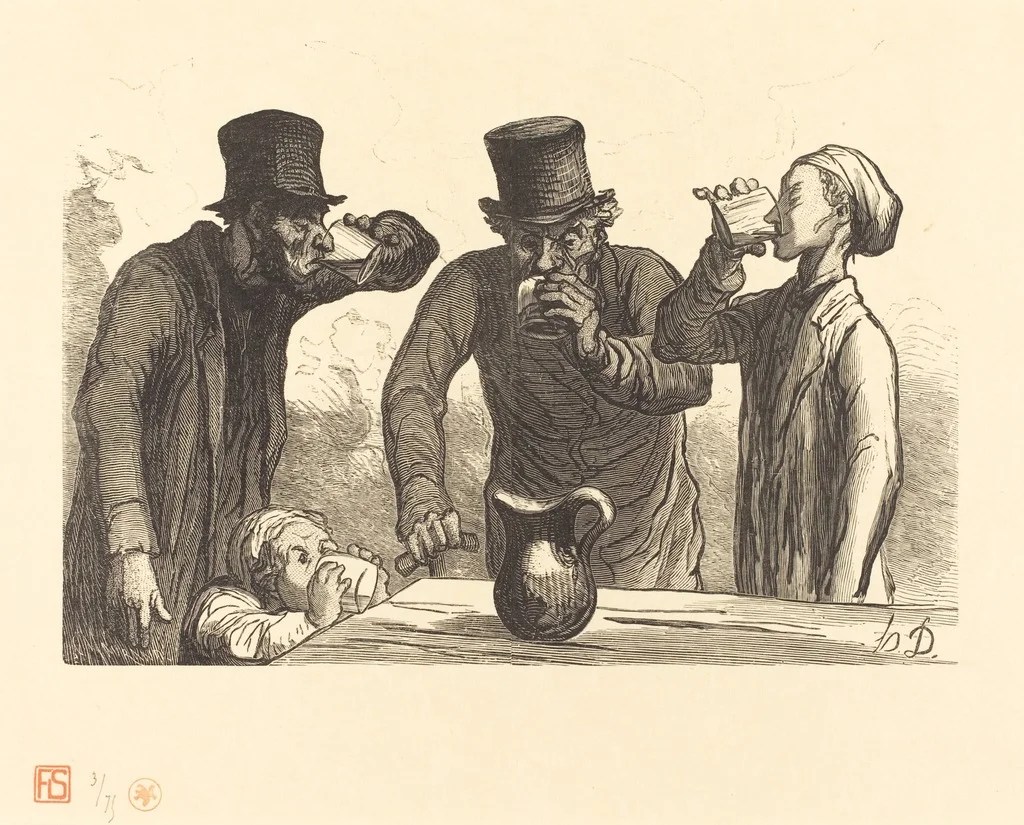

4. Vincent Van Gogh, The Drinkers (1890), Chicago

Van Gogh is one of those artists that seems so well known that he couldn’t have any surprises left, but of course that’s not the case. This picture caught my eye at the Art Institute of Chicago because it appears to show four generations drinking together, including a baby(!). Van Gogh’s painterly flourishes make it seem like a perfectly normal scene rendered in a way that was novel at the time, like the artist’s Bedroom in Arles or farm workers sleeping in the shadow of a mound of hay. But it’s not normal, it’s deeply weird! Is the baby drinking milk and imitating the men who seem to be drinking wine? Or is the baby drinking wine? It’s not clear. It wasn’t until later that I found out that the picture is a copy of an etching by Honoré Daumier called Physiology of the Drinker: The Four Ages (1862). Daumier was engaged with caricature and social commentary in a way that we don’t normally associate with Van Gogh, so in its original incarnation the picture is pretty clearly a commentary on the generational nature of alcoholism. Before this, I didn’t know that Van Gogh directly copied popular pictures of the day in order to render them in his style. The museum is full of surprises. Drink up, baby!

5. Anonymous sculpture at a luxury sunglasses shop, Manila

Doing my homework to write these descriptions typically makes me love the artworks even more. But that’s not the case with this sculpture. This is a very large, hyper-realistic figure of a man in a luxury sunglasses shop in Manila, and I like it less the more I learn about it. In fact, I kind of hate it. But I’m leaving it on the list anyway, because it left an impression on me, and I think it says something about the time and place where I saw it. I was in Manila to direct a short documentary for a few days, and most of the time we were on a university campus or in fairly poor areas, but the final night we went to a very posh shopping district in BGC (Bonifacio Global City) to get dinner. I spotted what I thought was a Ron Mueck sculpture in a store called Gentle Monster. I went in to investigate, but I could not confirm who the artist was. Researching later, I’ve learned that Gentle Monster is a South Korean luxury sunglasses brand that’s known for retail environments that feel like art galleries, including very large and elaborate sculptures. They have stores all over Asia and a few in the US and Europe. They have over “100 in-house artists” who make these overwrought promotional displays. On the one hand I’m grateful that these talented artisans are employed, but it’s also deeply sad that there’s no meaning in these objects beyond, “Wouldn’t it be cool if there was a really big guy in the store? Please buy a $300 pair of sunglasses.” It’s interesting that Gentle Monster is based in Korea, because the entire area felt very much like Seoul and not at all like the rest of Manila. Jeepneys, the gritty and creatively decorated minibuses that define Manila street culture are banned from the streets of BGC.

6. Unidentified Artist, Anagram of the Sweet Name of Mary (18th cent.), University of Notre Dame

In September I visited the lovely new art museum on Notre Dame’s campus, the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art. They had a lot of wonderful things on display and, not surprisingly, a lot of Catholic religious art. This piece caught my eye because even though it predates Western abstraction by two centuries, it’s not really pictorial, at least not in a traditional sense. The acronym MRA stands for the latin Maria Regina Angelorum, or “Mary, Queen of Angels.” It’s a picture of letters, floating and emitting light in some undefinable space, with little cherub heads, books, and scrolls flitting about. It reminded me of Jasper Johns’ paintings of letters and numbers, where the image of a thing and the thing itself are indistinguishable, because the subject (letters or digits) are both themselves and a sign for something else. It’s also a painting about the Virgin Mary that doesn’t picture her at all. Pretty weird.

7. Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Blessed Ludovica Albertoni (1671-74), Rome

I went to Rome in October to produce a short documentary about a scholar who is studying the acoustic qualities of sacred spaces. That meant I visited a lot of churches and cathedrals. In the Church of San Francesco a Ripa there was a side chapel that contained a marble funerary monument by Bernini. In fact, it’s said to be the last sculpture he completed on his own. This was a pleasant surprise. Bernini is a master, of course, so much so that it’s become something of a meme for people to post detail shots of his sculptures along with whiny questions about why people don’t make art like this anymore (realistic sculpture is now used to sell Korean sunglasses, see above). But the experience was also sort of funny. Viewers are not allowed to get close to the work. We weren’t just kept back a safe museum distance, the sculpture was at least 20 feet away, so appreciating the detail was a challenge. On the railing preventing viewers from getting close, there was a box with the poorly translated message, “OF LIGHTING OFFER,” with a slot where a one Euro coin could be inserted. Putting in a coin turned on lights which illuminated the sculpture slightly better than the daylight through the windows, which then turned off automatically after one minute. It reminded me of a Zoltar fortune teller machine, a kitschy parlor trick layered on top of one of the greatest sculptors of the Renaissance.

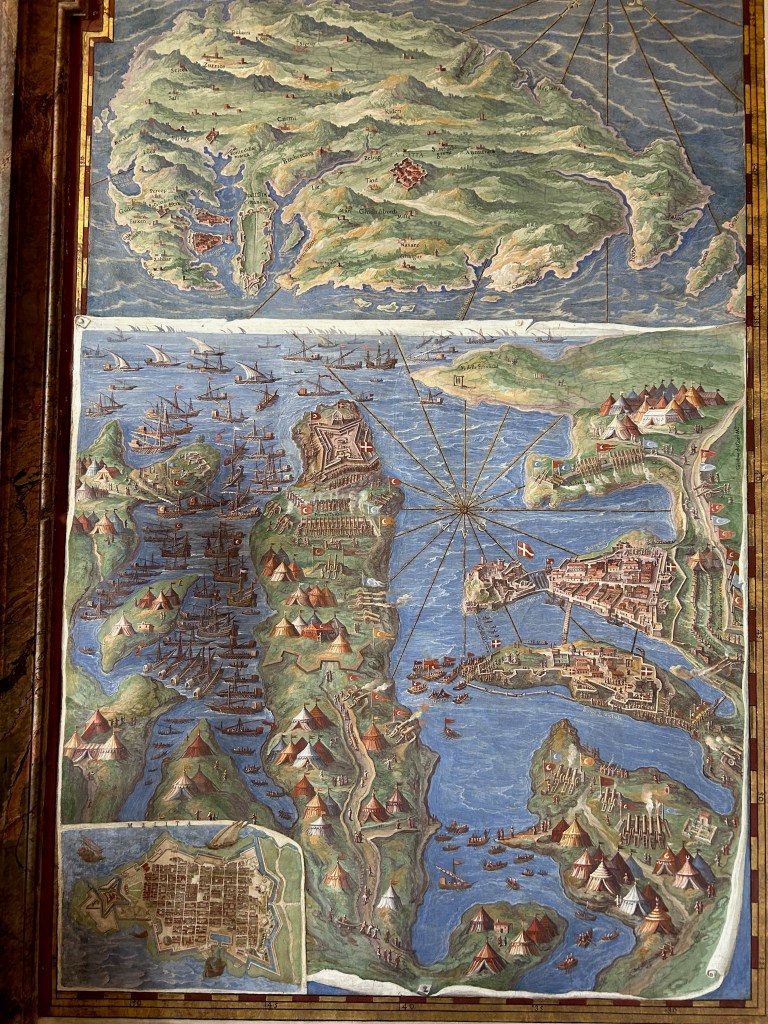

8. Ignazio Danti, Gallery of Maps (1580–83), Vatican Museum

When in Rome, we visited the Vatican Museum. I was excited for the Sistine Chapel ceiling (see below) but I was also curious about what else might be there. The museum is designed to lead visitors through a long series of galleries and halls before they can see the famous ceiling. This was an odd experience, as most people seemed to be part of tour groups that were moving way too fast to enjoy anything. The hordes shuffled past “boring” details like Raphael’s The School of Athens and what is probably Francis Bacon’s most flattering portrait of a pope. I tried to remain attentive and I was rewarded with the Gallery of Maps. It’s a very, very long hallway with frescoes of maps of every region of Italy as they were in 1580, when the works were commissioned. It’s such a pleasure to get lost in maps, particularly old ones. There’s also something magical about looking at maps that are so large that you have to walk to take them in, the hall is 120 meters long. Perceiving the map is its own journey.

9. Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel Ceiling (1508-12), Vatican Museum

It feels so corny to put this on the list. But damn, it lives up to the hype, it really is amazing. Seeing how Michelangelo rendered bodies, with volume and depth, looks like a sculptor decided to try his hand at painting and ended up doing it better than all the other painters. It’s also a disorienting way to look at a picture, by craning your neck and looking upward. It’s dizzying, literally and compositionally, because the image has no unified sense of up or down.

Wikipedia tells me that the Sistine Chapel is still a functional chapel, and that the Vatican uses it for very special meetings and masses. But when I was there it didn’t feel much like a holy space. As awe-inspiring as the frescoes are, you can’t escape the fact that you are crammed in there with a bunch of tourists. It struck me that a space could be so successful at fulfilling its purpose that its purpose is paradoxically destroyed. Here it is, the chapel containing the most iconic depiction of God creating Adam in Western art, a pinnacle of both art and Christianity, but it feels kind of like a theme park. It’s a space so holy that its holiness led to an ungodly amount of popularity, and that frantic, crowded, sweaty popularity saps it of holiness. It’s a victim of its own success, but it’s a beautiful ruin.

10. Hagia Sophia, (537), Istanbul

I didn’t plan to visit the bookends of the Roman Empire this year, but it worked out that way. Istanbul is amazing, and Hagia Sophia was the highlight. The structure was built as a Byzantine Christian Church in the sixth century. Back then what we now refer to as Byzantium was just the Eastern Roman Empire, which survived much longer than the Western part, and was centered in Constantinople until 1453, when the Ottoman Empire took over and changed the name of the city to Istanbul. Hagia Sophia is emblematic of this history. As the city became Istanbul, the church became a mosque. It remained a mosque until 1935, when the first president of the secular republic of Turkey turned it into an interfaith museum. It was a museum until 2020, when the current president, Erdoğan, turned it back into a functioning mosque, as a way to appease conservative Muslims. When we visited our Turkish hosts grumbled that it should still be a museum. The idea of a contested religious space going from church to mosque to museum and then reverting back to a mosque reminded me of Hito Steyerl’s 2016 essay where she recounts Russian separatists in Ukraine redeploying a soviet-era tank that had been on a pedestal at a military museum for decades. She says, “Apparently, the way into the museum—or even into history itself—is not a one-way street.”

Inside Hagia Sophia we were relegated to the second floor galleries, as the ground floor is only for Muslims who come to pray. The Byzantine mosaics of Mary and Jesus are stunning, but the highlight for me was the inscription in a stone railing made by a Viking sometime between the 9th and 11th centuries. The Norseman, named Halfdan, left a simple message: “Halfdan carved these runes.”

Dishonorable Mention: The Fake Pieta in St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City

I was with my wife in Rome and we decided to wait in an extremely long line to go inside St. Peter’s Basilica. It was my first time there, but my wife had visited decades earlier. She had seen Michelangelo’s Pieta back then, and she was determined to see it again. We spotted it as soon as we walked in, but something was off. The sculpture was set forward from the side chapel where it’s supposed to be housed, and it was in front of a temporary wall covered with fabric. Behind this wall was an area that was clearly undergoing renovations. A sign explained in multiple languages that new protective glass was being installed in advance of the Year of Jubilee, which is in 2025, but the sculpture we were looking at was not behind glass at all. The entire crowd gawking at the piece and snapping photos seems not to mind or notice, but something was clearly off. Although the replica was the exact size as the original, and the detailing was very good, the white surface just didn’t have the kind of lustre that you expect from marble. The odd thing was that the text never said clearly that we were looking at a replica, it only said that the protective glass was being replaced. The fake sculpture was surprisingly grotesque and uncanny, but the throngs of tourists didn’t seem to know or care.